Lessons from the Witchcraft School

And then I heard him say something that I instantly typed into my notes app on my phone "Follow me please, into the showers."

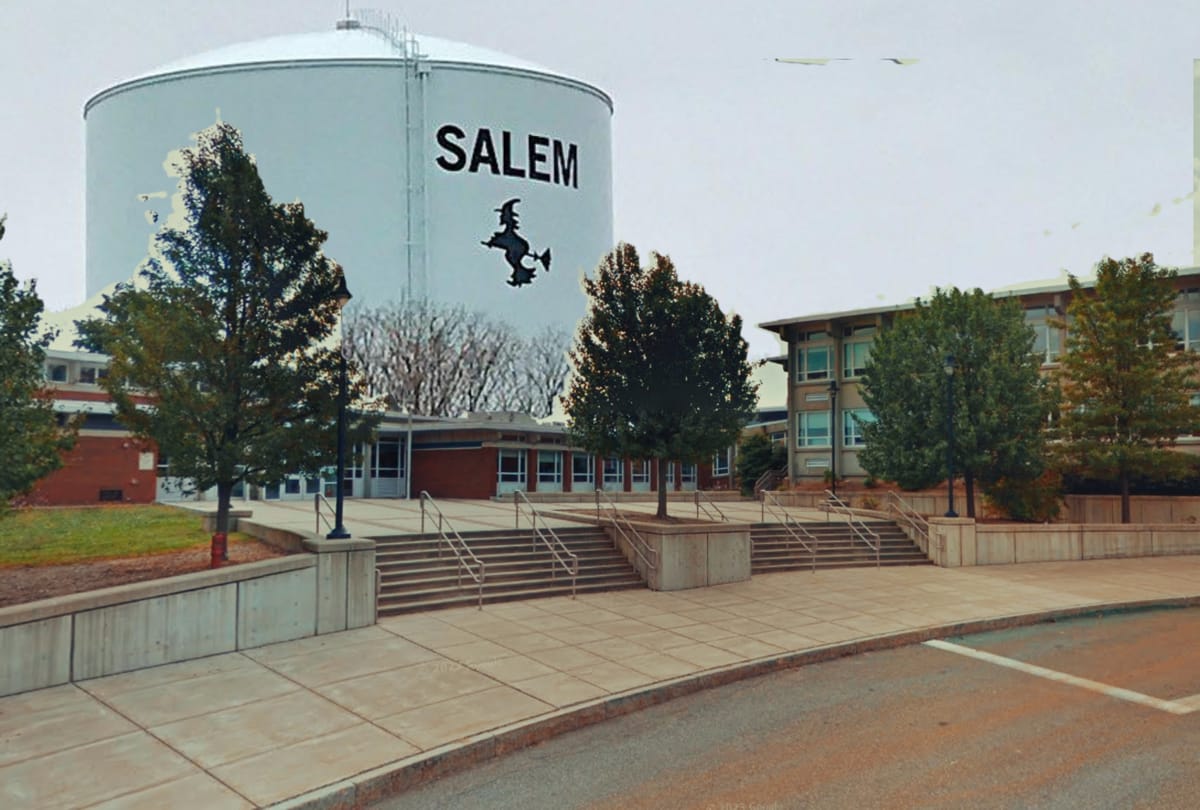

I grew up in Salem, Massachusetts and if you've heard of the place, you likely associate it with Halloween, Hocus Pocus, and of course, witches. I lived just outside of a new neighborhood built in the late 60s and early 70s called Witchcraft Heights.

As this sprawling suburb was one of the largest developments the city had ever approved, they required the developer to construct appropriate civil infrastructure, such as playgrounds, a sewer system, and a school. And the school was named after the development, thus the "Witchcraft Heights Elementary School."

On some maps, the name "Witchcraft Heights Elementary School" was too long, so they shortened it to "Witchcraft School," which, in the Internet age post Harry Potter, caught the attention of many mystery hunters. In the centuries hence, I wonder what curious people will make of the "Witchcraft School in Salem."

But it was just an ordinary elementary school, in a brand new and somewhat brutalist building on a hill in a modest city north of Boston.

We did embrace the "witch stuff." Our gym uniforms were black and orange, and the official logo of the school (and newspaper and police department) featured a "witch" atop a broomstick soaring in the sky.

By all reports, the education was far from top notch, but I didn't know any better. And I did learn some things. Many of them from the late Mrs. Pszenny.

Not all the things I learned were intentional.

She was a kindly yet serious woman, who my 10 year old eyes considered "older." I'm likely older now than she was then.

She loved maps, history and evidence. "Evidence is the proof, and proof is evidence!” she'd yell as she banged on her desk. Years later, I'd spend time examining that proclamation and find it wanting, but it did anchor a thought in my head: evidence, and thus the truth, are very important.

She's the first teacher to show us a text book and say "This is wrong."

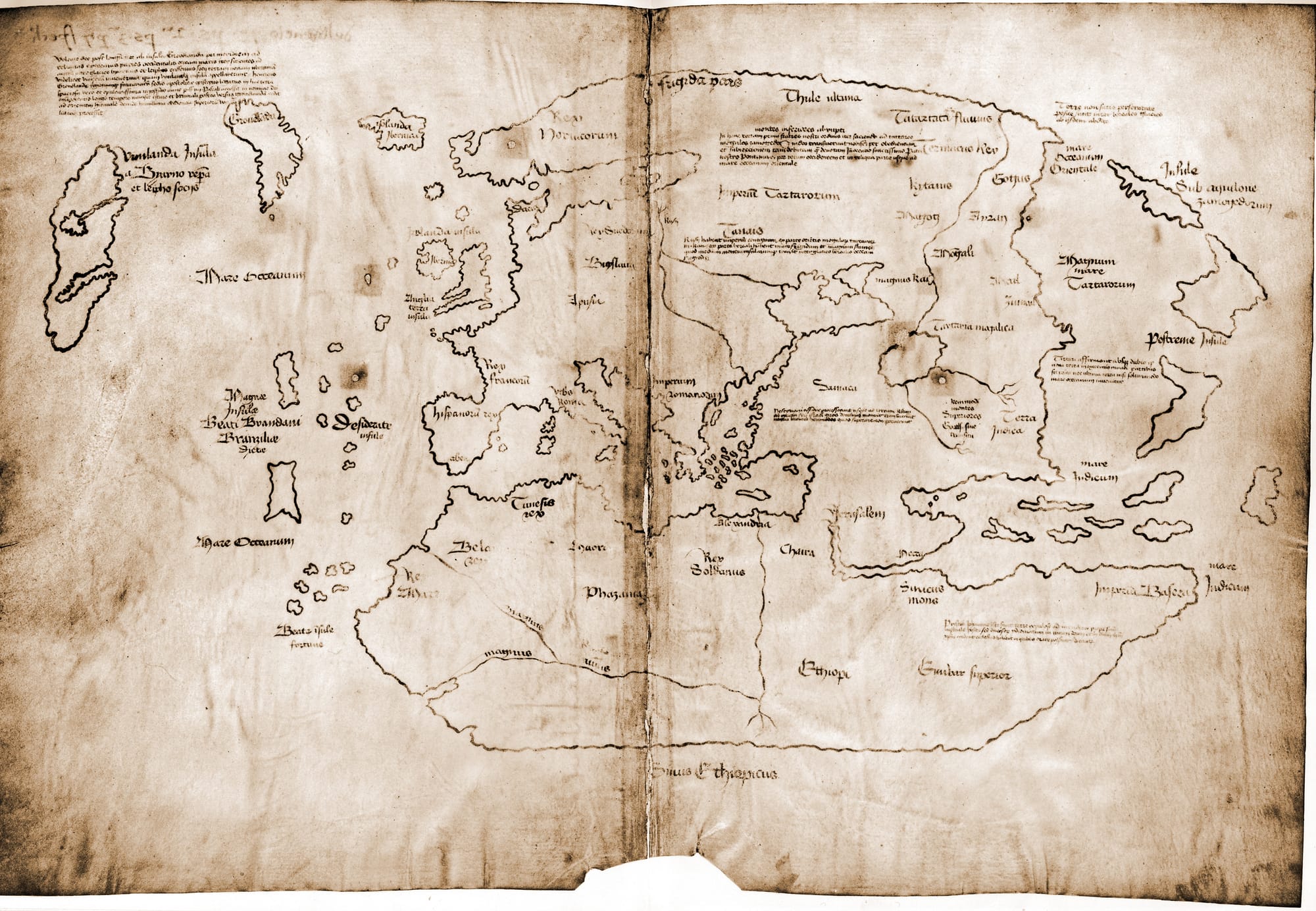

In her hands was a Social Studies book with a section on the Vinland Map. A remarkable document discovered in 1965, it's thought to have been created in the 1440s. It portrayed a detailed outline of Greenland, though it was made at a time where the coastlines and other features were covered by ice, and thus invisible. The text book said it was real, most scholars said it was real, and we had been conditioned all our lives to believe that everything in a text book was infallible.

There WAS "extraordinary" evidence to suggest it was real, such as the carbon dating of the paper (right time period), right kind of ink (oak gall, checks out) and even book worm holes that lined up with pages found in another 15th century work. Sagan would have been satisfied.

And yet here was this teacher saying "this isn't real." And she had a 1974 New York Times article to back her up. It took a long time for the world to catch up to her, but they did, and the map is now widely regarded as an elaborate hoax: too much titanium in the ink mixture managed to convince the few remaining believers.

For a 10-year old, this was powerful stuff. Books could be wrong! Smart people could disagree! And I began to look at everything with a skeptical eye.

And it was around then that I realized there was something terribly wrong in Salem. This was before Salem was "Halloween Town," as Haunted Happenings, a weekend festival that has now consumed the city year round, didn't cast its spell until the 1980s. Salem was a place where an awful thing happened, and most modern day activities celebrate or parody those tragic events. Buy our potions! See your aura! There's even a vampire shop.

Let's be clear: there were no witches in Salem. Ever. There was religious overreach, there were vulnerable people, and there was greed. And the power behind all that was fear.

Tituba, an enslaved person probably from South America may have done some things in the woods with the girls that one could call "witchcraft." We really don't know what court Tituba held, but what she was probably doing was sharing her culture. And to the Puritans, anything straying from their long thin lines of authority was "witchcraft."

Most folks come to Salem today not to learn from history, but to enter a fantasy that directly mocks the false accusations that dozens of people died for. The victims were by and large Christians who were not in favor of witchcraft, and it's striking that people don't remember who the victims were, but instead flaunt a caricature of who they were accused of being.

And that leads me to the Czech Republic.

I recently had the chance to tour a bit of Czechia (locals told me to call it The Czech Republic), and a side trip visiting Terezín, an 18th century fortress town named after the ubiquitous Empress Maria Theresa. Today, it's best known as the site of a concentration camp during World War 2.

When I hear "concentration camp," I think of Schindler's List, Viktor Frankl, Ann Frank, and Life is Beautiful. Terezín was something different. It was definitely a concentration camp, and the atrocities that occurred there are more than any peaceful mind can bear, but it was more of a clearing house than a final destination. It was also famous for being set up as a Potemkin Village for Red Cross inspectors, who found the place austere, but up to humanitarian standards. The incarcerated had regular meals, relatively comfortable sleeping arrangements, tidy bathroom facilities and recreational opportunities.

And it was all a lie.

It's a compelling story, and I encourage you to look into it.

On the day of the tour, we boarded the bus and the guide said "Unfortunately, today we are going to Terezín." She was Czech and spoke English clearly, but with an accent (mentioned for a reason). The day before, she'd been our guide for a beer tasting in Prague.

Having visited the Holocaust Museum in Washington D.C. not long after it opened, I had some idea of what I was in for. The visit would be impactful, challenging, and important—but not fun. I was going not to be entertained, but to be educated in a way that only a visit could furnish. I wasn't looking forward to it, but I felt obligated to go simply because I want to make an attempt to be human.

As we made our way though the countryside, she passed around some materials—pictures of buildings, maps, photos of some Nazis—and I looked at them, but couldn't really absorb them. The camp or ghetto was not one structure or fenced in area, but many, spread throughout a town where people lived. How could non-incarcerated people live in a concentration camp? I figured I'd understand once I got there.

We arrived in a large parking area, much like you'd find outside any major attraction. But save for the restroom facilities, there were no buildings nearby; just a path that led towards a giant Christian cross. As we got closer, I could see that we were walking by a massive cemetery, and there was a large star of David as well as the cross. And my first thought was—the segregation continues. Christians here, Jews there. But there was no commentary during this part of the tour, so I wasn't sure if I was missing a more important message. We walked on.

Passing through a gate, things looked more like I was expecting—rows of low buildings acting as walls, unadorned and full of right angles. A sign said "Suvenýry." Below that, right above a large arrow the word "Souvenirs" translated the Czech into both old and new lingua Franca.

Yes, even in a concentration camp, you exit past the gift shop.

Behind the sign, a machine selling commemorative coins with engraved images of the cemetery asked for 3 Euros. Hmm. As we were waiting for the Terezín guide to appear, we went into the gift shop.

I went through the door with the thought "What could possibly be in a concentration camp gift shop?" But inside, I saw that the building was mostly a staging area for school groups (Good - they brought school groups here). There were photos of various Nazis on the walls, and indeed, a small "gift" shop, but it would have been better described as a book store. Perhaps a few dozen different works on World War II and concentration camps lined the walls, mostly printed in Czech. A plaque outside showed that this was originally the canteen for Nazis, and a few intricate coffee vending machines keep that tradition alive.

Directly visible from the exit of the gift shop was an archway, with the notorious German phrase "Arbeit Macht Frei" emblazoned upon fresh white paint. This had obviously been repainted since WW2, after all, once the camp was liberated it was used for other things until 1996. I realized that the experience we were about to have was heavily curated. It would have been de-converted back to 1945 at least.

Our guide appeared.

He was a 20 or 30-something Czech man, also with clear English and a recognizable accent. He greeted the group in a somewhat cheerier way than our bus guide. I expected him to start with a summation of what a somber place we were about to visit, but his tone throughout the tour, and his whole demeanor, was that of someone giving a tour of a formal garden or pretzel factory. It didn't seem to match the enormity of emotion I expected to experience.

But - maybe I'm just coloring too much. After all, I'd been thinking about this place for months, and had gone through many mental exercises to prepare for it. Plus, he wasn't a native English speaker—it's very possible I was interpreting his non-literal cues through a biased and even damaged lens. Was the tone intentional? Obscured through an accent? If I could speak Czech (or German), would I have a different experience?

I resolved to remain in observational mode.

He told the story of Karl Rahm, "...an evil man, even by Nazi standards." He dropped on the gallows four hours after his guilty verdict, and that's fine with me. But again, the tone in which it was said seemed off. It reminded me of something, and it took me a while to realize it, but it reminded me of the tone of ghost tour guides. It was... lurid. And again, I'm probably wrong in this assessment, but that's what I experienced.

The guide led us through room after room, each with its own horrific stories. Hundreds of men crammed into a small room, only the a suggestion of sanitary facilities, hard shelves for sleeping, if there was any, and solitary confinement cells that looked much better than the general population space to me.

As we entered each room, the guide described various tortures the prisoners would endure. I'll spare you most of them, but he talked about how prisoners would be starved for as long as possible and then treated to a feast of salted bread. Very, very salty, but the prisoners were allowed to eat as much as they liked. And eat they did, for they were starving. And then they were put back in the cells, and denied access to water. They died with insatiable thirst.

And then I heard him say something that I instantly typed into the notes app on my phone:

"Follow me please, into the showers."

Again, this wasn't Auschwitz. Tens of thousands of people died here, but only a relative few were executed. For that, the incarcerated were sent to the large processing centers like Auschwitz. These showers never had Zyklon B in them, but the equipment left behind (and the story of how they weren't really used) made them menacing.

At this point, I was convinced that this tour was designed for entertainment rather than education. And maybe that's what most tourists want—I know it's often what I'm looking for. But this was the site of one of* the most horrific acts committed in the 20th century. Surely it deserved a more reverent tone?

The tour changed from entering one dark and uncomfortable room after another to a brief tour of the fortress the camp was built in. This was interesting, and we were allowed to explore a section of the miles of tunnels that offered defending soldiers endless opportunities to fire upon attackers (that never came). I'd like to tour again and just focus on the history of the fort, but I was not there for that, and my emotions became more confused.

Finally, our last stop was a grassy area surrounded a massive brick wall. On the ground were several concrete pits filled with sand, looking very much like the crosses of Calvary, laid down. The guide explained how the wall was used for executions, and how just before the Soviets were to finally liberate the camp, the Prague gestapo, who was in charge of the prison, ordered the deaths of 52 Jews. They were lined up on the very wall we were looking at and shot, just days before they were to be set free.

No explanation was given as to why this was, or why this group of men. And no explanation was given to the crosses on the ground. This angered me, as here we are in a place of tragedy, with an obvious religious symbol on the ground—how could this not be part of the tour?

So I asked, what are these crosses? And at first, he didn't know what I meant, so I pointed and he said "Oh, that's where they set up the guns for the firing range."

What I saw as crosses, he correctly saw as simple sand pits for soldiers to lie in and take aim. Perhaps my bias was too strong.

But then we walked to the gallows, which were obviously not original to the 1940s. The wood was fresh and undamaged, which seems impossible for something 80 years old.

Then he told his final story.

The gallows were constructed for the execution of one man who had escaped and been captured. Despite all the death in this place, the gallows was not commonly used, but, according to the guide, the Nazis had developed a superstition about it. It was supposedly cursed, and anyone who touched it would die within the year. And while I certainly hope that was true for the Nazis (it certainly was for those who touched in 1945), I gave up all pretense of being in "observational mode" and marched straight to the cursed object, and embraced it. I turned back to the group, and noticed folks taking my picture. The guide looked on, but said nothing. After a few moments, I let loose my embrace and returned to the group, remaining silent for the rest of the tour. Should I die before November 20, 2025, you'll know that I still wasn't cursed, it was just a coincidence.

A childish act? Sure, but I'd do it again.

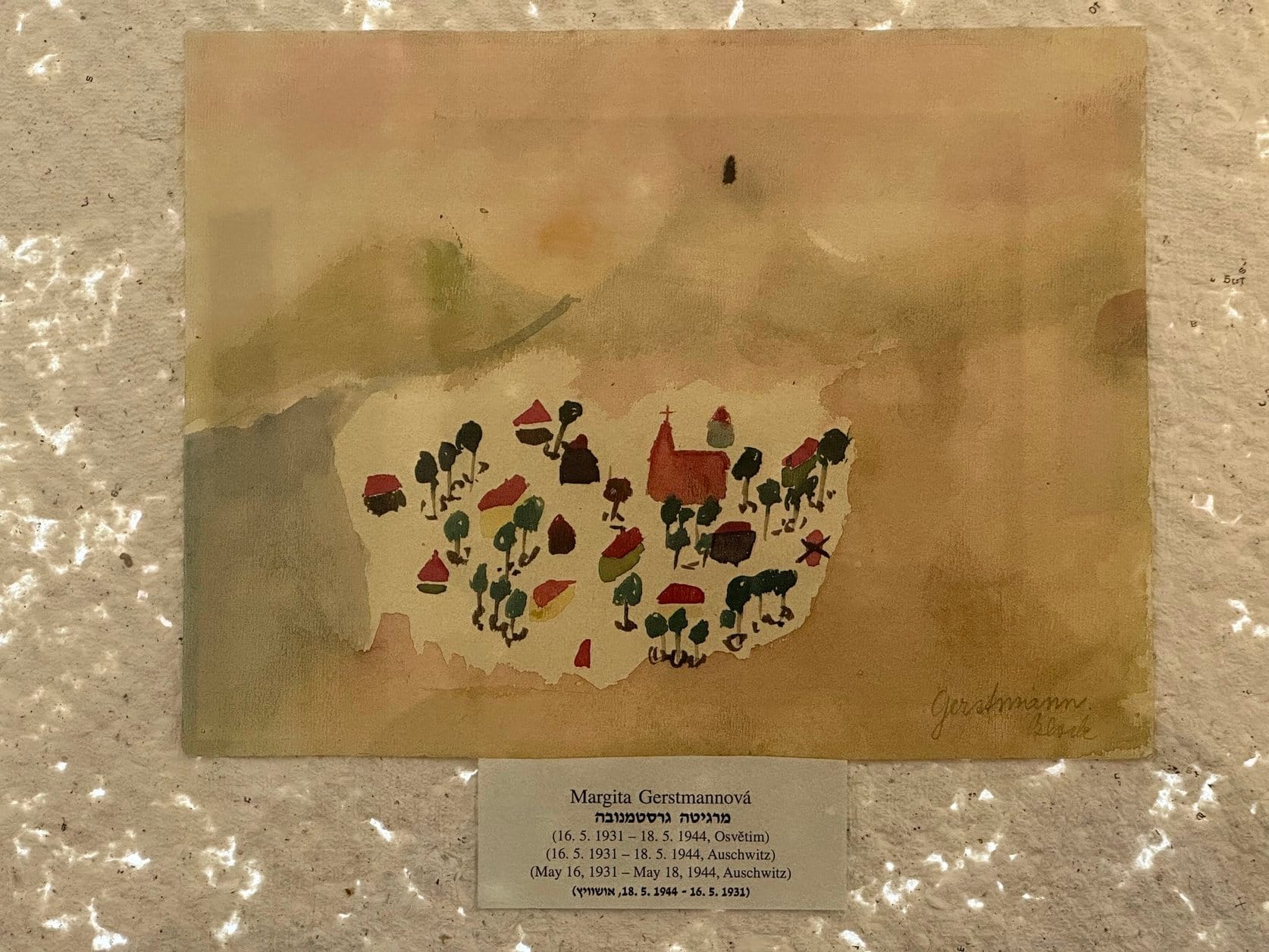

After another visit to the gift shop, we loaded onto the bus for a short ride to a school in the town. It was now a museum, filled with art, a major portion of which was created by the children who lived there during WW2. Nearly all of them died in camps. This had the impact I was expecting, but it was unguided and we were rushed through to watch the propaganda video. We could watch this at any time, but this was our only opportunity to understand the school.

Deflated and confused, I returned to the bus and napped on the way back to Prague.

The tour of Terezín bugged me. But I couldn't quite figure out why.

Was it the same as what Donna said in the blog NomadWomen?

"And I am shocked to realize that I am disappointed.

Disappointed that it was not more cruel? More inhuman? Disappointed that I will not be able to see face-to-face how barbaric we as a race can be to each other? Sorry that I will not get the entire effect of the brutality of war thrown in my face?"

Yes, that's certainly part of it. I didn't get the emotions or challenges that I expected. By the time we got to the school, I was in such a state of mind that I could recognize the impact, but couldn't entirely feel it. If we had started there, or, radically, made that the only stop, I think the experience would have made made sense.

But that wasn't it entirely. It was the "ghost tour demeanor" of the tour guide that really stuck with me: a light mention of the history, gross detail of the prurient, and no summation of what this all means.

And meaning was what I was after.

Not mentioned was the fact that Viktor Frankl, author of the remarkable book Man's Search for Meaning, was incarcerated at Theresienstadt, as Terezín was called then. What's more, his father died there, giving him yet another thing to overcome, which his book shows that he did. The book is about meaning! Our tour to Terezín lacked it completely.

"Oh the stories they could have told us!" my friend Liz James said on Facebook. She took the necessary step of digging deeper into the history and meaning of what we'd experienced. For example, the men chosen for execution in those final days weren't chosen randomly, and some survived. They simply ignored the guards when their name was called.

Gavrilo Princip was a prisoner at Terezín during World War One, and while we saw his cell, we didn't learn much about his time there—or why he assassinated Duke Ferdinand in the first place: thus starting WW1, which arguably started WW2. It would be unfair to place the two world wars at this wretched man's feet, but there is a direct path.

The tour could have been SO much more.

But again, my lens is cracked. And there's the practicality that many who visit this place think of WW2 as being as distant as the dinosaurs. The topic is so big and so horrifying that it's impossible to encompass it all in a 90 minute tour. I am being too harsh.

And yet, I'm still bugged.

This morning January 2, 2025, while I stared into the grout of my own shower, waiting for the water to get cold which would force me to finish my business and get out, I realized the final piece of what troubled me about this tour: I'm afraid that some day, Terezín could end up like Salem. It could become a place of tourism rather than a memorial to an enormous conspiracy of injustice.

It's not close to that now—there are no "Medieval Torture Museums" or party restaurants in Terezín. But as people get further and further away from a personal connection to such places, the holocaust could join the age of piracy, the Spanish inquisition, or the Shogun period as things people mock for fun without any real sense of the horrors they themselves have avoided.

And tourism will let that happen. Tourism is not about education. Most tour guides are entertainers, not educators. And they will tell the story that most people want to hear.

Gruesome statistics, horrific details—but no lesson. No admonition of "don't do as we did!" Just an endless stream of shareholders, entitled tourists, and narratives crafted not for accuracy or enlightenment, but for excitement.

I learned at the "Witchcraft School" that the truth matters, but it seems entertainment matters more.

Thanks for reading.

~ Jeff Wagg

*It’s striking that I need to refer to the Holocaust as only “one of” the most horrific acts of the 20th century. Too many others compete for that title.