a wound turned into light

An hour ago, Jen and I were at an art exhibit. Or perhaps it was a gallery, or a show or an entire museum. I'm not exactly sure what the proper analogy is, but I know it was art. Fine art. The best kind of art, at least for me.

In this particular museum, the walls are horizontal. You sit beneath the wall, and highly-trained people place each artwork in front of you. After a period of time, they replace it with another. And another. Until you've taken a journey through the artist's mind.

And yes, I'm talking about a restaurant. But I'm talking about art, not food.

To explain a meal at Alinea in effective detail is to unweave the rainbow and defeat its purpose. What's more, my wife's birthday dinner wasn't at Alinea (which is the name for a paragraph mark), it was at Next, a different restaurant that switches themes every few months. The current theme: the first year's menu at Alinea in honor of their 20th season serving curious patrons.

I'm not going to write about those restaurants, though. It's too big of a topic and I'd have too much to explain. You can find out a whole lot about them online, and you'll find out who Grant Achatz is. You may already know: he's one of the most famous chefs in the world, and we in Chicago are fortunate enough to have several of his establishments to enjoy. Both Alinea and Next are his creations.

Instead, I would like to talk about a pond in or near St. Clair, Michigan.

St. Clair is a suburb of Detroit, right on the Canada line. If you're not familiar with Michigan's geography, Canada is to the East of St. Clair. The "Great White North" is actually the "pretty-much-like-here" East in this region.

I've never been there, but I do know some things.

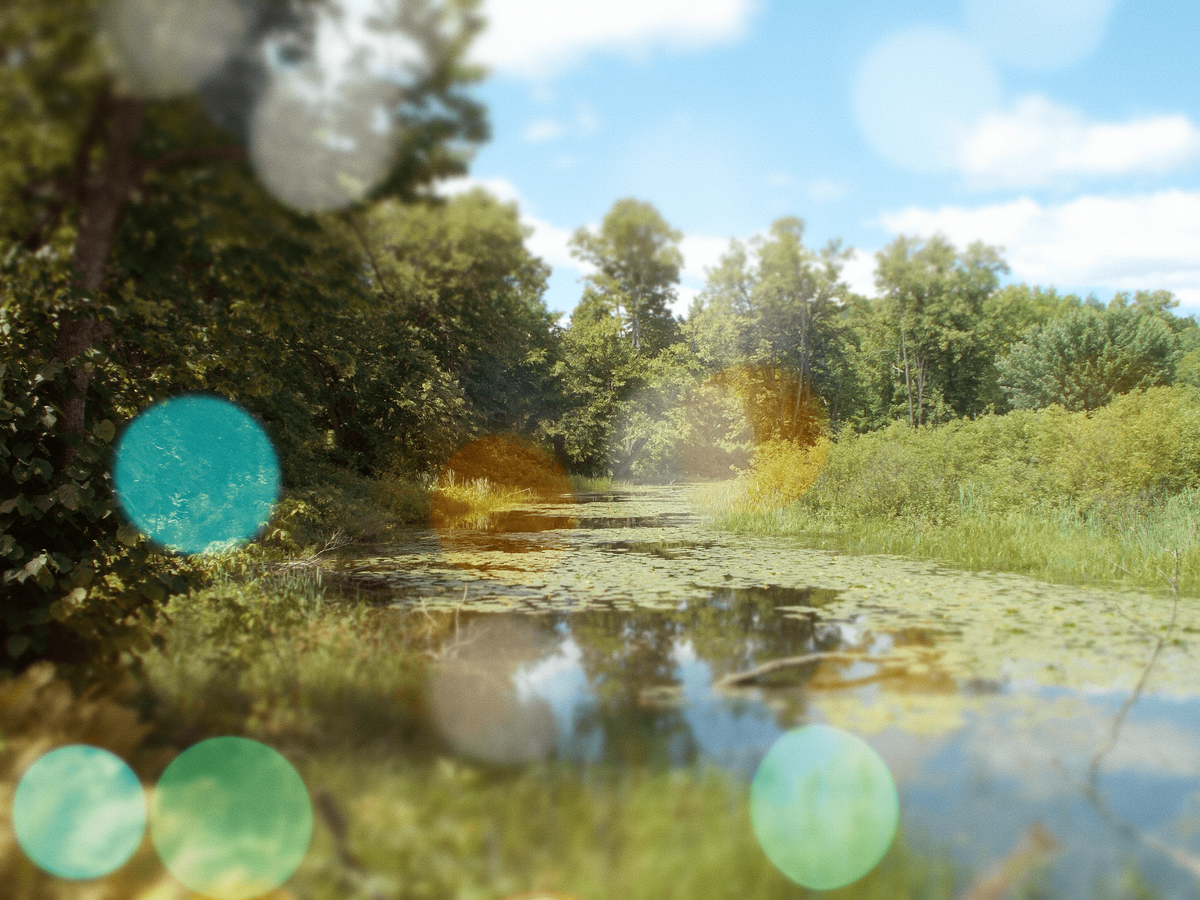

In the early 1980s, a boy about 10 years old was playing in a forest, mucking around in a pond, skipping stones, catching frogs, and learning about scents, sounds, textures. He knew how the wind felt when a high pressure system moved through and charged everything with an energy that made him feel alive. He figured out just how much pressure is required to hold a frog so it didn't get away, and he wondered who would ever want to eat frog legs. Could he do it? He wondered about that a lot.

After his adventures, he'd come home, wash off mud and pine tar—maybe not very well—and lay in bed staring at the ceiling while crickets chimed and fireflies flashed. He may have had some in a jar on his dresser next to a C-3PO figure with a missing arm.

Years later, he'd leave that place and have many adventures in Chicago and then LA, and then around the world. But he never forgot his time in the muck amongst the mosquitoes and brush.

I have never met the boy-now-man, and I've never been to St. Clair, but I know his experience intimately. Because he showed me with his art.

Food as art can be a cliche or it can be skeuomorphic, like a cake shaped like a volcano or a watermelon carved into a canoe. Those are akin to graphic art, where the form is the whole of the meaning. The art I'm talking about would feel at home in the MOMA.

Obviously, the boy is Chef Achatz, but I feel like calling him a "chef" misses the point of what he's doing. He's creating art, and it's a multi-sensorial experience. If you attend one of his restaurants because you want a good meal, you may be surprised to learn that it's more than that. It's not a meal. It's an entire experience, and food is merely the medium.

And I did mean "attend." The experience counts as theater as well as object-based art. You get both. And nutrition too.

I'm not making this comparison to praise his cooking. "It's like fine art!" No, I'm directly and unequivocally saying that what Chef Achatz does is art in its highest form. And I think modern art is the best framework for understanding his work.

Molecular gastronomy, as it's often called, has gained popularity since it first graced plates and raised eyebrows in the late 1980s. It's characterized by many small portions, each being a new creation made with unexpected ingredients.

These small plate adventures are now featured on cruise ships, to show just how "mainstream" this form of dining has become. But dining at Wonderland on a Royal Caribbean Ship or even in Eden on Celebrity is akin to visiting an art store at the mall, if there are any left. Sure, there's some interesting stuff in there, but you're unlikely to experience what you can experience the depths of emotion available at the Art Institute or Guggenheim.

Jen and I experienced a 10 year old boy doing what 10 year old boys are built for though art. At least I did. Jen probably had a different and also pleasurable encounter.

When Achatz created the menu for Alinea in the early 2000s, he took inspiration from many places in his past. Some dishes reflected what he learned at The French Laundry. Others are experimentations with newly invented cooking techniques and odd combinations of ingredients. Olives and coffee? Yes, that can work. And he shows us how. But some pieces achieve the goal of art: they make us feel.

Achatz doesn't think of dining as an experience of merely flavor. Of course it is that, but he knows that we have far more than five senses, and he wants to access them all. When the highly choreographed servers (and it feels diminishing to use that term) present a dish, they explain how to experience it. Start here, do this, notice these things. They nearly always mention what you're supposed to smell. How you'll feel the cold and hot together, working against each other with a common purpose. The mint doesn't belong there, but it's essential for telling the story of how the chocolate and avocado work together on a bed of burnt coconut.

An Achatz meal excites your sense of taste but it can also changes your philosophy. Reading over the ingredients, you may think "this shouldn't be good," and maybe it isn't. But it's interesting. It's making me feel something. And that's the only definition of "art" that really matters.

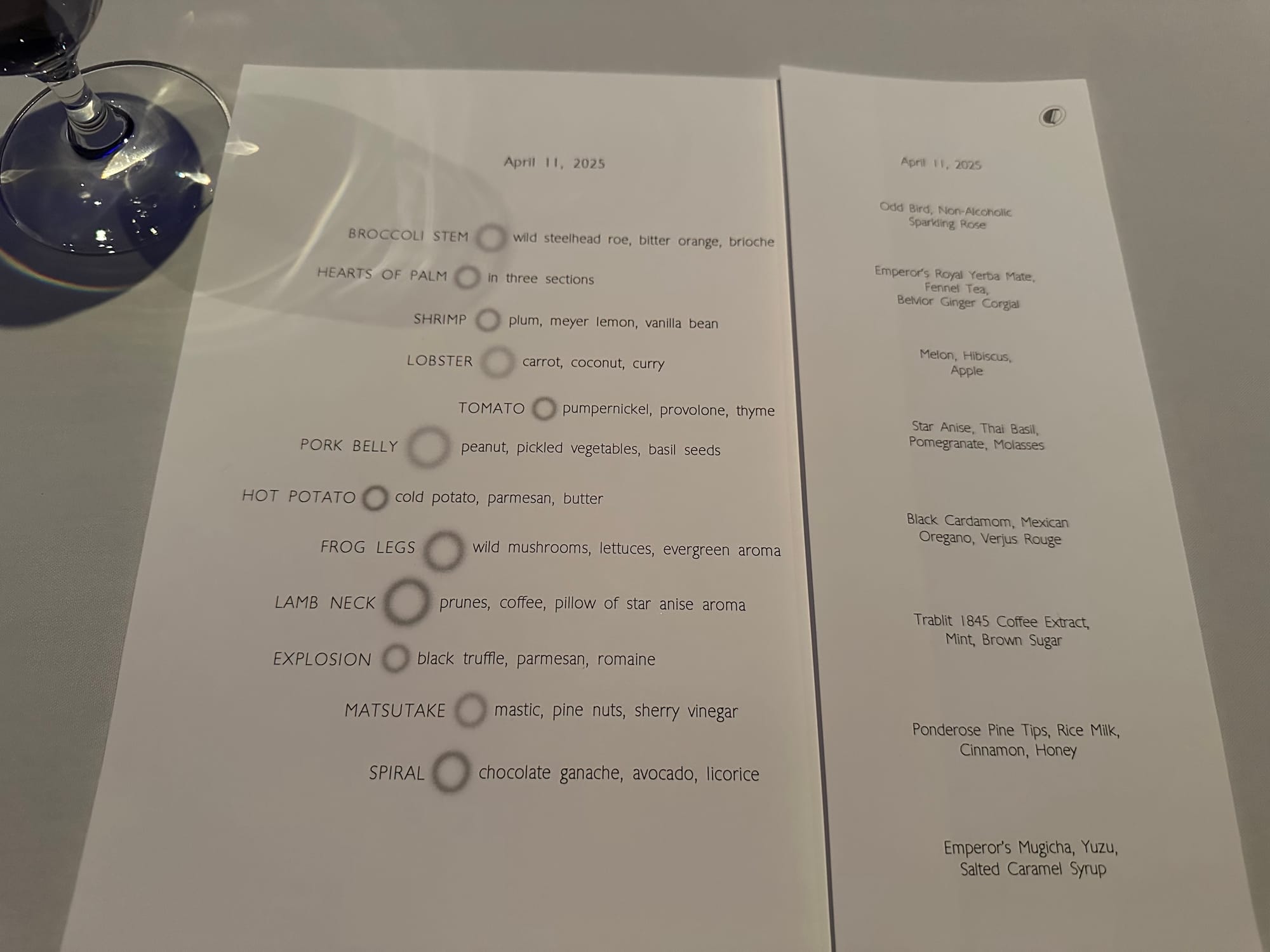

I saved the menu from tonight's experience, and I share it with you here. I had the non-alcoholic drink tasting, which deserves its own battery of blog posts, but they'll never be written.

Each course is a simple thing, like a Picasso—just cotton canvas and paint.

You might see the word "mastic" on there. I know mastic as construction adhesive. Tonight I learned it's an edible resin from a pistachio tree.

But this is the line that inspired me to type so many words:

Imagine what that dish is like.

I did, and I thought it would be frogs legs on a plate, in their classic diamond pose, grilled or fried with a bit of a rustic salad and maybe a sprig of spruce to give it a bit of interest.

It wasn't that.

It was a 10 year old boy and his pond.

The server gave us a warning as he put the the deformed-oval bowl in front us, at a specific angle. "There's more to this dish coming. Please wait."

I took in what was in front of me. The deep bowl was filled with foam, like spittle bugs on tall grass or frog spawn at the edge of a marsh. There were leaves, round, like lily pads, floating in the foam. On the edge was an orange nasturtium resembling a Canada lily, commonly found in Michigan wetlands. There were some breaded parts underneath, but before I could determine what they were, another server came with a pot of hot water.

When the original server placed the bowl in front of us, it came on a plate or charger that was covered with balsam fir, another common bit of flora from the Michigan/Canada border. It looked very much like a Christmas centerpiece, with long springs of fresh evergreens.

"The hot water will release the aroma of the forest, calling back to Chef's time as a boy hunting frogs in the ponds of his Michigan childhood." The water poured, the needles stirred, and time shifted.

Waves of sweet pine scent swam up and reminded me of times in my own childhood, exploring the woods of New Hampshire.

"Everything is edible, except the pine. Enjoy!"

We explored the environment in front of us.

The foam was a pond, and also the pond scum at the edges, and frog spawn, and spittle bug nests. It had a complex savory taste, with rich hints of ocean funk. The lily pads were watercress leaves, and served as miniature carriers for bits of foam as they slipped into the spoon. The nasturtium was surrounded by various lettuce leaves, and for them, the foam served as a dressing.

Beneath, were the frogs. Hiding.

You see, you had to hunt for them...

The frog legs themselves were boneless and fried, and tasted like the best chicken nuggets I've ever had. Again, a call back to childhood. But they weren't the frogs in this metaphor! The frogs were firm bits of mushroom, lurking beneath the surface. They were slippery and evasive, and when I captured one on my fork, it felt like an accomplishment. With a chewy and weird texture, they called up ideas of what a child's idea of eating a frog would be like.

It was a dish that made me feel nostalgic, though I'd never had any of these things before, at least not like this. And it inspired me to spend the evening writing this.

Jen enjoyed the dish too, but I don't think she had the same experience I did. She didn't have the same childhood, after all. The art spoke to me. The food spoke to her. Both responses are valid and good.

I did not a take a picture. As soon as the dish was placed before me, I reached for me phone, and then put it away. It didn't seem right somehow. I wanted to live in THAT moment, a moment that took me back to the simple joy of being in nature and exploring things in a visceral way that's often denied us in adulthood.

But I know you're curious, so I dug around and found an image. This picture, from a reddit thread about Chicago food, doesn't do the experience justice. For one thing, the lily pad effect isn't there—instead of a few small, round leaves, this version has one large leaf, which doesn't quite capture the feel of lily pads.

And the person who took the photo found the dish I just spent a few hours writing about, inedible.

Modern art is not for everyone.

Here's the photo:

There are a few other photos out there as well, and none of them impress me as much as the actual thing I consumed.

You're free to think whatever you'd like, but I had an enjoyable experience this evening, and I thought I'd share it. I do think food can be art, and this hit the mark for me. It won't for everyone.

I'm remarkably fortunate to be married to such a wonderful woman who's not only willing, but eager to share experiences like this with me. It's my favorite thing, and I'd trade all the art in the world to spend evenings with her.

Thankfully, I don't have to.

French artist Georges Braque, a close colleague of Picasso, once said "Art is a wound turned into light." I think Chef Achatz did just that for me tonight. His wound in this case is a nostalgia for his Michigan childhood, and that resonates with me. I hope from time to time, you can find something that resonates with you.